The Making Of…Wardrobe, 1755

It’s been my practice to make at least one new piece each time the Slim Shady series is mounted to ensure that the exhibiting gallery has some new work to “debut”. In 2010 I upped the ante. I would incorporate the history of the exhibiting gallery and/or the history of the gallery’s location into the new work.

Usually a piece starts with a rough or simple idea. I begin physical work on the figure(s) and research is conducted throughout the making of the piece as required. Layers of meaning are added as the idea/work becomes more and more complex.

New works inspired by the exhibiting region begin differently. For the Acadia U piece I began with the gallery’s location in Wolfville.

Wolfville is a stone’s throw from Grand-Pré, an area steeped in fascinating history. I immediately became interested in the Acadians and le Grand Dérangement. I read books, surfed online, watched documentaries, and listened to traditional Acadian music. I absorbed as much information as I could, took notes when I needed to, and when I felt the information had percolated enough I started sketching out ideas in my sketchbook:

During my research I came to the conclusion that there were five characters integral to the Acadian narrative which I needed to include in my finished piece: a British soldier, a French soldier, a First Nations man (Mi’kmaq), an Acadian man (a nod to Gabriel from Longfellow’s Evangeline), and an Acadian woman (a nod to Longfellow’s Evangeline). The identities of the figures would be defined by the superficial signifier of traditional dress with attention to the time period of 1755.

The presentation I finally settled on was a wall-mounted composition with the figures hung off miniature hangers inside a closet-like framework:

I don’t ever recall learning about le Grand Dérangement in history class and I thought of it as one of Canada’s dirty little secrets, a skeleton in Canada’s closet (to be fair, Canada wasn’t yet Canada at the time).

I don’t normally like to divulge the meaning behind every little detail in a piece; I feel doing so is akin to saying, “Hey, there’s this great movie you have to see…and this is how it ends.” I prefer to let people discover the stories behind the narrative I’m presenting on their own, but in the interest of disclosure, here goes…

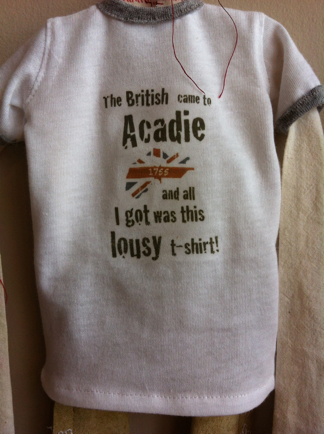

The unstuffed, clothed figures became skins, not skeletons. Most of the heads are brutally removed and resting on posts above the bodies, reminiscent of hats on a top closet shelf. The figure’s feet have received a similar treatment, with most of the feet arranged on a shelf cum shoe rack. The “soldiers” bookend the other figures, all three of whom are caught in the middle of the British/French struggle for Acadie. The Acadian man and woman are separated from one another, referencing the physical division of families during the upheaval. Front and centre is the Mi’kmaq, wearing traditional leggings but sporting a cheesy souvenir t-shirt that states: “the British came to Acadie and all I got was this lousy t-shirt”. The integration of an item of clothing from pop culture bridges past with present:

The t-shirt suggests the negative influence of non-native culture on indigenous peoples. Its statement refers to all that was taken from First Nations people and the small recompense they received in return. The word “lousy” is not just a comment on the quality of the souvenir, it also references the introduction of deadly diseases through contact with, and products of, the Europeans. The title, “Wardrobe, 1755” simultaneously refers to the war taking place, a place for storing clothes, and the collection of suits contained therein. The decorative lines of the wooden shelves are inspired by the Acadian Deportation Cross.

Construction was a multi-step process. First I had to draft patterns for shirts, chemise, pants, military jackets, skirts, and hats. I sketched patterns on newsprint, using a combination of acquired know-how and trial and error. The more complicated items, such as the turnback coats, required a muslin test or two to be made before embarking on the final garment in fine Italian wool.

I obtained new levels of obsessiveness when I fabricated 80 miniature buttons (with some help from my artist friend, Tzaddi) using two types of scrapbooking brads…

…and yes, those buttonholes are all fully functional. 🙂

Creating the Brown Bess musket that sits on the upper shelf introduced a new skill – carving:

Initially I was going to purchase a pre-made scale model, but I couldn’t source the right firearm in the correct scale. I found a schematic online for a Brown Bess that showed side, top, and bottom views that aided immensely in the carving and detail finishing of the balsa wood version I made:

From the start of research to the finished product took over 310 hours; one of the most labour-intensive pieces in the series to date and one of the most rewarding to create.

Tomorrow: the Fredericton piece.

[…] So I tried an experiment. On January 7th I “advertised” one of my recent blog posts (The Making of…Wardrobe 1755) on Twitter and Facebook – something I’d never tried before. When I checked analytics […]

Ah shucks, Tzaddi [scuffs foot across floor].

You are too kind (but I love hearing it – say it again!).

Hmmm, now I’m thinking that the making of those little buttons may have been made more tolerable by the ingesting of Tiny Bubbles…

Have I told you lately how freaking AMAZING your work is?

I am remembering all those little buttons and now I have a song in my head “Tiiiiny Buttons… Make me happy… Make me warm all over…”